Thoughts on Failure Courtesy of The Bauhaus

In three years’ time, Germany will celebrate the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the Staatliches Bauhaus. This event will involve endless design exhibitions, talks, debates and panels not to mention a wash of merchandising. All this for an experiment, which by its own standards, failed.

Last weekend, I was privy to a tour of the newly opened The Bauhaus #itsalldesign exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art led by curator Jolanthe Kugler. Kugler, curator at the German Vitra Design Museum, has spent the past several years becoming an expert on all things Bauhaus. As she led us around the various rooms of the exhibition, she spoke of the contemporary phenomenon that is “The Bauhaus”.

German for “Construction House”, Bauhaus existed for fourteen years (1919-1933) in Weimar. During that time, it switched cities and directors three times each. The Bauhaus community included industrial, interior and textile designers, architects and choreographers. Students turned masters and masters turned celebrities.The number of female enrollees was strictly limited due to a perceived threat that so many women were interested, they might take over.

Photo via Carlos Castro on flickr

The tenure of this revolutionary and iconic arts school was short and volatile, no one could agree on what the school stood for or what the outcome of it should be. The aesthetic was up in the air, open to interpretation. In Kugler’s words, there was “not one Bauhaus but many Bauhauses.”

As we reached the end of the exhibit, which includes Bauhaus furniture, toys, kitchenware and posters, Kugler casually threw out that the Bauhaus dissipated in 1933 when those in charge realized that the Bauhaus goal was not possible.

“They wanted to create beautiful, functional objects that the ordinary person could afford to purchase.” Ikea comes to mind here. “Essentially, they failed at this. Their items could not be mass produced and, in the rare moments that they did manage to produce large quantities of something, like the famous Bauhaus wallpaper, it was incredibly expensive.”

Although the school was an enormous success, students were falling over themselves to get in and the masters’ outpourings instant hits, the realization that the audience was comprised only of the elite was enough of a blow to knock down the entire house.

This unusual and incomprehensible clash of failure and success is riveting.

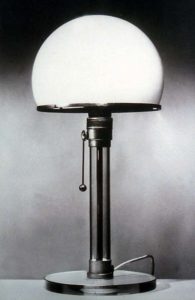

The most obvious example of this contradiction of intention and outcome, which is on display, is the Bauhaus Lamp. For decades, the Bauhaus lamp has been a staple amongst fashionable and design savvy homeowners. Designed by Wilhelm Wagefeld in 1924, the lamp boasts an elegant white glass dome perched on top of a clear white stem. In its original state, if not handled with great care, the lamp cracked, fell apart or stopped working altogether. It could not be mass produced or sold because its materials were precious. Today, a newly engineered and more stable Bauhaus Lamp can be purchased for just shy of $1,000 at the Moma store, the perfect antonym to the Bauhaus cause.

Bauhaus Lamp via Maryellen McFadden on flickr

Did the directors of Bauhaus, Walter Gropius, Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe, anticipate the colossal success and impact of the Bauhaus brand? Or did they finish out their respective stays at the school defeated?

Given the choice between failing at one’s original goal but achieving greatness and fulfilling one’s mission, I’d go with greatness hands down.

If Bauhaus was a failure, what’s so great about success?